Wari'

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- Linguistic family

The Wari’ are often referred to as Pakaa Nova, as they were first sighted on the river of the same name, an affluent of the right bank of the Mamoré river in Rondônia state. But they prefer to be called Wari’, a word meaning ‘people’ or ‘us’ in their language: this is how they are known to the ‘civilized people’ (as they refer to Whites in Portuguese) who live in closest proximity to them. Today they live in villages built around seven Funai ("Fundação Nacional do Índio" - National Indian Foundation, governmental agency) Posts administrated by the Guajará-Mirim Support Team in Rondônia, as well as within the Sagarana Indigenous Territory, at the confluence of the Mamoré and Guaporé rivers, administrated by the Diocese of Guajará-Mirim.

The Txapakura peoples

The Wari’ comprise one of the few remaining peoples of the Txapakura linguistic family, as most of those speaking languages belonging to this family had already become extinct by the start of the 20th century. Today only four Txapakura groups exist: the Wari’, the Torá, the Moré or Itenes – who live on the left bank of the Guaporé river, a little above its confluence with the Mamoré, in Bolivia – and finally the OroWin.

The latter were encountered in 1963 in the region formed by the headwaters of the Pacaas Novos river, and were almost exterminated in two attacks made by Whites. No more than a dozen adults and a few children survive, now living in the village at the São Luis Indigenous Post (IP) on the upper Pacaas Novos. A few people calling themselves Cujubim also exist, scattered between Sagarana village, the Sotério IP and the town of Guajará-Mirim; they only speak a few words of their language, but enough for us to know that it belongs to the same family.

The reports available on the Txapakura peoples are fragmentary and vague: travelers record their presence and describe their relations with Whites, occasionally noting certain aspects of their material culture. Only the groups known as Huanyam, or ‘Chapakura’, and the Moré were visited by ethnographers.

According to the ethnologist Curt Nimuendajú, the geographical center of the Txapakura peoples appears to have been located on either shore of the lower and middle courses of the Guaporé river, although some groups, such as the Torá and the extinct Urupá, were associated with the Madeira river and its affluents from the 18th and 19th centuries onwards. Many of the Txapakura peoples already had contacts with Whites in the 17th century; they lived in Spanish and Portuguese missions, formed alliances with Whites, escaped and were captured or were wiped out by epidemics and armed attacks.

Location and population

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Wari’ occupied the following region in the southwest of Amazonia: the basin of the Lage river, an affluent of the right bank of the Mamoré, the basins of the Ouro Preto river, the Gruta and Santo André creeks and the Negro river (all affluents of the lower and middle courses of the right bank of the Pacaas Novos river), as well as the Ribeirão and Formoso rivers. Around this period, part of the population migrated to the Dois Irmãos and Novo rivers, affluents of the left bank of the Pacaas Novos.

Following land invasion by rubber tappers during the first decades of the 20th century, the Wari’ relocated to the headwaters of rivers, areas which were more difficult to access, until the moment when they were ‘pacified’ by missionaries and agents from the SPI ("Serviço de Proteção ao Índio" - Indian Protection Service, the governmental agency preceding Funai): this took place between the end of the 1950s and the start of the 1960s. Reduced by epidemics to at least half their original population, the Wari’ settled next to the SPI’s posts within a few years.

Nowadays they live in eight settlements, located in five different Indigenous Territories within Rondônia state, as shown in the diagram below. The Sagarana Indigenous Territory, where the settlement of the same name is located, administrated by the Diocese of Guajará-Mirim, is the only territory still to be approved (its legal situation remains ‘Delimited’).

From first contacts to 'pacification'

The Wari’ were mentioned for the first time by Colonel Ricardo France in 1798, located on the shores of the Pacaas Novos river. However, they remained in isolation until the start of the 20th century, possibly because they lived in areas that were difficult to reach or attracting little economic interest. All this changed with the discovery of the process for vulcanizing rubber in the middle of the 19th century: this provoked a massive rush in search of the raw material in the forests. The Madeira river was chosen as a main access route. Construction of the Madeira-Mamoré railway was started, with the aim of linking the locality of Santo Antônio on the Madeira river to Guajará-Mirim, from where the extracted latex would be transported to Manaus. 1919 saw the first documented clash between the Wari’ and railway workers, who abducted numerous Indians and took them to be displayed in the town. In 1912 – the very same year the railway was inaugurated – there was an abrupt drop in the interest in Brazilian latex, as it became supplanted economically by Malaysian production. Many rubber tappers had to abandon their activities, and the Wari’ – who had been forced to relocate to more inaccessible territories around the headwaters of the rivers – were able to re-occupy some of the past village sites.

In the 1940s, following occupation of Malaysia by the Japanese, the second rubber boom took place, and many rubber tappers started to move up the Pacaas Novos river and its tributary, the Ouro Preto, so that by 1950 the former was the most densely occupied affluent of the Mamoré. This was the peak of the conflicts between the Wari’ and the ‘civilized peoples.’ Rubber plantation owners organized extermination expeditions in which villages were attacked at dawn, sometimes using machine guns and killing a large proportion of their inhabitants. The Wari’ were not slow in seeking revenge: rubber tappers and railway workers were found dead with their bodies riddled with arrows. The tension of the conflict forced the IPS into remedial action, beginning the process of ‘pacification’ with the setting up of ‘attraction posts’ in various localities.

The first peaceful contact was established only in 1956, with the participation of fundamentalist missionaries from the Brazilian New Tribes Mission. At the time of contact, the Wari’ occupied villages situated along the Lage river (an affluent of the right bank of the Mamoré) and its affluents, on the headwaters of the Ribeirão river, on tributaries of the right bank of the Pacaas Novos river (upper Ouro Preto, Mana to’, Santo André creek, Negro river and its affluent, the Ocaia) and finally on the Dois Irmãos river, an affluent of the left bank of the same river. The ‘pacification’ process lasted over ten years (until 1969, when the last isolated Indians were re-settled): the Wari’ had been dispersed over a vast territory and, even after settling at the Posts, returned to the forest whenever they felt threatened, especially by epidemics which killed more than two-thirds of the population during the contact period.

The local groups and subgroups

The Wari’ have no name that refers to the group as a whole – that is, no name for the social unit usually referred to as ‘a tribe’ or, in more modern fashion, as ‘an ethnic group.’ The word wari’ designates the pronoun for the first person plural inclusive, ‘we,’ which also means ‘human being,’ people.’ This is the form by which they are known regionally and how they prefer to be called by Whites.

The widest ethnic unit defined by them corresponds to what we refer to here as a subgroup. There is no generic name for subgroup, only for ‘a person from another subgroup,’ tatirim, which we translate as ‘stranger’.

Each subgroup has a name. Today these comprise the OroNao, OroEo, OroAt, OroMon, OroWaram and OroWaramXijein (oro is a collectivizing particle that can be translated as ‘people’ or ‘group’). Some individuals identify themselves with two other subgroups that no longer exist: the OroJowin and the OroKaoOroWaji.

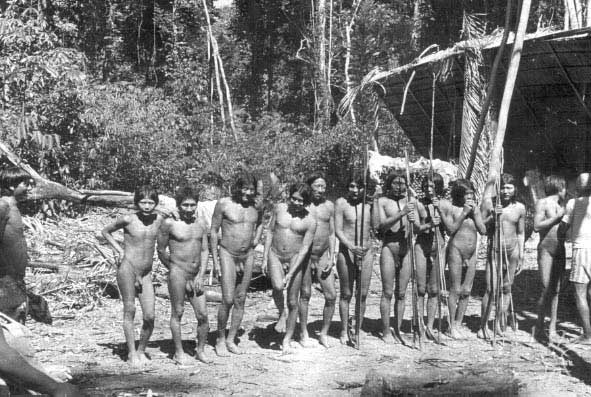

Each subgroup was linked until the moment of ‘pacification’ – and in part still today– to a specific territory, consisting of a set of named areas, inhabited by local groups. The local groups possessed a set of brothers as a nucleus, very often married to a group of sisters. Polygyny, especially sororal polygyny (that is, simultaneous marriage to one or more of the wife’s sisters) was frequent. It was usual for the couple to vary their place of residence, sometimes living with the woman’s parents, sometimes with the man’s parents. As a result, it is impossible to define a rule of residence. A group would stay at the same location for one to five years: after this period, its composition and the site of the settlement would change. The village settlements were always located on the Amazonian terra firma, away from flooded areas and by the shores of small year-round rivers. Villages were made up of a set of houses occupied by nuclear families and a men’s house, which functioned as a dormitory for single adolescents and a meeting place for adult men.

There was always a maize swidden on the outskirts of the village: this provided the Wari’’s staple crop. In actuality, it was availability of the soil type favorable to maize cultivation – black earth – which determined where the village would be located.

The association of the subgroup to the territory is something insistently stressed by the Wari’, and the antonym of ‘stranger,’ tatirim, a member of another subgroup, is ‘land fellow,’ win ma. But the frontiers of these territories were fluid: if a particular area normally associated with one subgroup came to be occupied by a set of people whose nucleus was made up of men from another subgroup, this area would then become recognized as the latter’s territory.

There is no clear rule defining membership of a subgroup. Children are said to belong to either the father’s or the mother’s subgroup, or to the subgroup linked with the territory in which they were born. The identity of a person is gradually constituted during their life, through communal living with their co-residents, especially through commensality. Despite appearances, this does not mean that the Wari’ assume that affiliation to a subgroup can vary during a person’s lifetime. Instead, any individual possesses a kind of multiple identity, where different people classify a particular individual in different ways.

Their current distribution illustrates the type of relationship the Wari’ establish between physical space and the subgroup as a unit. The subgroups from the time of pacification are sill in existence today. The Wari’ name themselves as OroEo, OroAt, OroNao, OroWaram, OroMon and OroWaramXijein. The majority of the OroEo and OroAt and some of the OroNao live at the Negro-Ocaia post, which is situated on the border of the territory once occupied by the OroNao and close to the land of the OroEo and OroAt. Another section of the OroNao live on the left shore of the Pacaas Novos river, where they relocated at the end of the 19th century, occupying the Santo André and Tanajura posts. Most of the OroWaram live at the Lage post, close to the territory where the OroWaramXijein formerly lived, while most of the OroMon live at the Ribeirão post, a region that the Wari’ occupied sporadically in the past and where they hunted, but without ever clearing swiddens. Part of the OroWaramXijein live with the OroWaram on the Lage, while another part live with the OroMon on the Ribeirão. When an outsider or stranger refers to the Lage post, he or she calls it the land of the OroWaram. Wari’ going to the Lage post for a festival say: “I’ll dance at the OroWaram.”

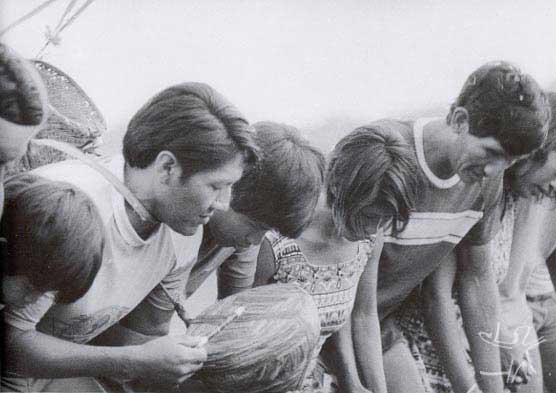

The different subgroups are linked to each other ritually by means of three kinds of festivals: tamara, hüroroin and hwitop. In general terms, hosts from one subgroup prepare chicha (a maize drink), which may be fermented (hüroroin and hwitop) or non-fermented (tamara): this is offered to the guests from another subgroup. The relationship between guests and hosts is one of ritualized hostility, where the latter seek to make the former drunk and humiliate them, as a form of punishment for having initially acted as predators of the hosts: disguised as animals or attacking their hosts’ animals and flirting with their wives. When a guest falls unconscious from excessive drinking, the host in front of him exclaims: “I killed him!” Today, these festivals are performed by residents of different posts who, as we saw, are associated with distinct subgroups.

Wari’ society is strongly egalitarian, without chiefs, age groups, ritual groups or specialists of any kind.

Warfare

Enemies are thought to be Wari’ who spatially distanced themselves and with whom exchange was interrupted. The Wari’ equate enemies with animal prey. In the past, when the Wari’ practiced warfare, enemies were killed with arrows and whenever possible parts of them were taken to the villages of the killers (all those who had taken part in the expedition) to be eaten by the women and by those who had remained at home. On returning, the killers entered a period of seclusion, remaining for most of the time in their hammocks in the men’s house and avoiding excessive movements and especially injuries, so as to keep the dead enemy’s blood within their bodies.

This blood – associated with the unfermented chicha, which made up practically the men’s only alimentary intake – fattened the killers, making them strong and virile. Sexual activity was also prohibited during this period: it would lead to the loss of the enemy’s blood as it turned into semen, which would then fatten their wives and lovers rather than themselves.

As he contained the dead enemy’s blood within himself, the killer was proscribed from eating his victim (or ‘prey’) as this would amount to an act of self-cannibalism and so provoke his own death. All other people, with the exception of children, could eat the enemy’s flesh, which was roasted and consumed in large pieces. This practice marked the difference between this meal and funerary cannibalism, by associating it with the consumption of animal prey.

Seclusion ended when the women announced they were tired of continuously preparing large batches of chicha, and when the men felt they were sufficiently fattened. Afterwards, the spirit of the dead enemy remained associated with the killer, just like a son: it followed him everywhere and ate his food.

Traditionally, the Wari’ engaged in warfare with neighboring peoples, mostly Txapakura and Tupi. The enemies most cited by them are the Tupian Karipuna and the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau. With the invasion of their lands by rubber tappers at the start of the 20th century, they lost contact with these enemies and warfare came to be targeted against the Whites, also classified as enemies, wijam. This war lasted until ‘pacification’ and acted as one of its main motives: faced with the mutilated bodies of neighbors and kin – very often killed by the Wari’ in retaliation for armed dawn attacks that massacred their villages – the government agents and powerful locals hurried to attract the Wari’, not just to put a stop to the killings, but primarily to open a route for expanding local economic activities, especially rubber extraction.

Funerary cannibalism

The Wari’ not only ate the enemies they killed – they also ate their own dead. The rite began with the onset of serious illness, when consanguine kin and affines wept for the dying person. This was followed by a funeral song in which everyone referred to the dying or dead person by consanguine terms and recollected events they had experienced together during the person’s lifetime.

After death, the weeping became more intense. Close kin – called ‘true kin’ – were at this point differentiated from ‘distant kin,’ a category which particularly included those effectively related by marriage. The former organized the funeral, while the latter executed it. Preparation of the corpse had to await the arrival of close kin who lived in other villages and who had received news of the death by means of these same affines.

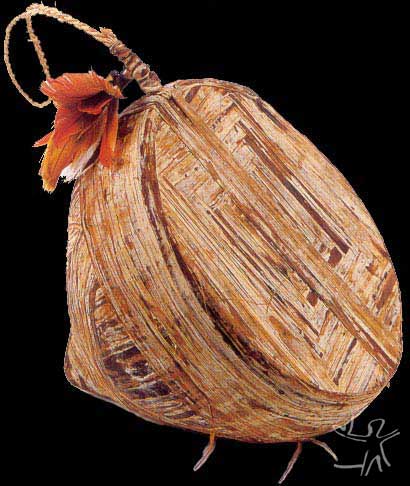

During this two or three day period, the corpse would start to rot: this was the state in which it was cut up and barbecued by the affines. When the meat was ready, close kin shredded it and place it on top of a woven mat, next to small prices of roasted maize cake. They then asked the distant kin to eat it. People had to avoid touching the meat with their hands: instead they used small wooden skewers to place it delicately into their mouths.

The Wari’ disliked any sign of the deceased being eaten avidly, as though it was game meat. Its rotten state – which apparently resulted from an inevitable prolongation of the wake, since kin living further afield demanded to see the corpse while it was still whole – was also a way of making ingestion of the meat unpleasant, sometimes nearly impossible. In these cases, only a small part was eaten and the rest burned along with the hair, internal organs (except for the liver and heart which were eaten) and genitalia.

When the meat was finished, the deceased’s close kin decided whether the bones would be burned and buried with the barbecue grill, or macerated and consumed with honey. In general, distant kin consumed the bones, but some people claim that this part of the meal was reserved for grandchildren, who were also the favored consumers of the deceased’s roasted brains.

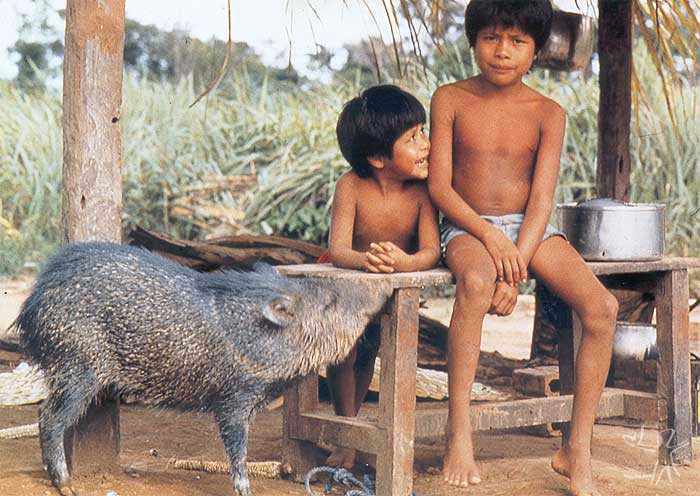

After the funeral, the ‘clean-up’ period started, when all the deceased’s belongings were burnt, including the house he or she constructed, the place where the body had been roasted, the person’s maize swidden and the places in the forest where he or she used to walk and sit. A prolonged mourning period followed, lasting several months or even years. This ended at different times for different kin, who decided when they should return to speaking normally and participating in festivals. These kin then performed the mourning closure rite: here, a large quantity of barbecued prey – killed during a collective hunt – was lamented as though it were the deceased. These prey animals were then eaten not only by non-kin but by close consanguines too. After this meal, people sang and danced and life subsequently returned to normal. The dead person’s spirit went to live entirely in the subaquatic world of the dead, which still happens today. When the dead come back to earth to see their own, they turn into white-lipped peccaries, who are hunted and eaten by the Wari’, and then return to the world of the dead.

Today the dead are no longer eaten, but buried after two or three days of mourning. Abandonment of cannibalism occurred shortly after ‘pacification.

Cosmology

The dynamic structuring Wari’ social relations – the contrast between the enmity related to killing and devouring, and the sociability related to food exchanges, marriages and mutual cooperation – is extended to the relationships with other beings.

Many animal species, as well as a few plants and certain natural phenomena, are considered human as they possess spirit. Most of the mythology, rituals and curative procedures involve the idea that as these beings are human, the Wari’ can communicate with them and treat them just as they treat other kinds of people.

Ancestral and animal spirits are the most important categories of spirit for the Wari’. Although they recognize the existence of other types of beings endowed with spirit – such as plants, thunder and mythic personae – ideas about their humanity tend to be vague, in contrast to the imagery relating to ancestors and animal spirits.

The spirits of the dead reside in a parallel society formed by villages situated under the waters of deep rivers, in areas occupied by the Wari’ subgroups before contact. The leader of this subaquatic world of the dead is a giant called Towira Towira. He is the ultimate cause of death among the Wari’, since he receives the spirit of seriously ill people in a hüroroin basket and, as host, offers them fermented maize chicha which, if accepted, causes the definitive death of the physical body. Following the mode of ritualized relationships of hostility between hosts and guests in Wari’ festivals, this encounter with Towira Towira is conceived as a form of symbolic predation followed by consumption and later resurrection of the prey, since the dead revive under the water. In turn, the Wari’ consume these subaquatic spirits, since when the ancestors emerge, they do so in the form of white-lipped peccaries. Like guests at a festival, the peccary-dead frequently approach a hunter who is close kin, so that its meat will go to feed its own kinsfolk. In this way, the offering of food and mutual help making up the core of Wari’ family life continues after death, transformed into a relationship in which the living and dead, humans and animals, alternate their positions of host and guest, predator and prey.

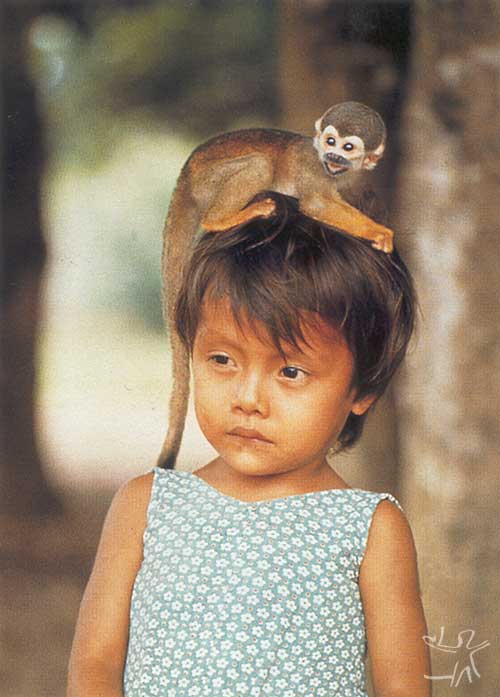

Themes of reciprocity and predation also permeate Wari’ ideas concerning those animals that possess human spirit, the jami karawa. This category includes deer, white-lipped peccaries, collared peccaries, tapirs, capuchin monkeys, jaguars, fish, bees and snakes, as well as some other species, depending on the informant’s subgroup. The jami karawa live in communities organized into subgroups, following the pattern of Wari’ villages previous to contact; they live in houses, cultivate swiddens and hold festivals. The Wari’ see the jami karawa as animals, but the latter see themselves as humans and the Wari’ as animals or enemies. The jami karawa provoke sickness by attacking the Wari’, shooting them magically with arrows or entering their bodies and eaten them from within: the result is the animalization of the victim. In the case of jaguars and snakes, predation focuses on the physical body of the victim and not the person’s spirit. In turn, the Wari’ kill jami karawa, since these animals comprise the types of game most appreciated by them. Before contact, various kinds of animals were prohibited as food, but alimentary restrictions are less rigid nowadays.

Shamanic practices fell into decline in the first years following contact, but a revival occurred at the start of the 1980s. In most villages, many families continue to depend on shamans for the treatment of illnesses caused by animal spirits, since only the shaman has the special vision enabling him to diagnose the sickness and see the jami karawa in their true form – as humans with which they can negotiate. Practically all shamans are men, and idioms from hunting, warfare and affinity permeate Wari’ discourse on shamanism and animal spirits. A man becomes a shaman when a jami karawa kills him and subsequently revives him – a process typically associated with a serious illness or trauma. When the animal spirit takes fruit or other substances from its own body and implants them in the body of a Wari’, it provides this person with shamanic powers and a double identity: he becomes simultaneously human and an animal of the same species which initiated him. Shamans treat those sicknesses caused by animal spirits and Wari’ sorcerers. They do not generally cure illnesses identified as White illnesses: these are usually treated by auxiliary nurses, nurses or doctors, using Western curing techniques.

Health, diet and economy

The most common health problems are malaria (which sometimes reaches epidemic levels), respiratory infections, parasitic infections, diarrhea and gastro-intestinal illnesses. Tuberculosis – including resistant forms – has also been a recurrent problem. Health conditions have varied radically over the years, depending on the level of medical assistance, especially in the villages.

Currently, each post settlement has a small pharmacy where primary medical assistance is provided under the supervision of an auxiliary nurse employed by the government agency, Young Wari’ have recently started to receive training as healthcare assistants, a model already in operation for some time in the Sagarana village. They then work in their own settlements, alongside the auxiliary nurses or even alone when the latter are absent. Functionaries from Funai’s Indian House in Guajará-Mirim provide more specialized diagnoses and treatments and coordinate vaccination programs, as well as the work of a group made up by a doctor, nurse and dentist which periodically visits the Wari’ villages, Between 1983 and 1989, the "Projeto Polonoroeste" (Northwest Pole Project) subsidized improvements to the medical infrastructure, including construction of pharmacy-hospitals in the villages, schools and houses for Funai’s functionaries, as well as the acquisition of boats, outboard motors, trucks, radios and generators for the indigenous posts. Following the end of these subsidies, medical and other services have suffered constant cutbacks and have been forced to depend on sporadic and uncertain funding.

The nutritional state of the majority of the Wari’ varies between adequate and precarious. Since contact. the Wari’ have adopted different cultigens, including bitter manioc, rice and various fruit crops, as well as domestic animals such as dogs and chickens. Cattle have been introduced in various villages, but raising them has proved unsuccessful. Children attending the schools at the posts receive daily lunches, while Wari’ families consume some industrialized foodstuffs, although subsistence still depends largely on hunt game, fish, wild foods and swidden crops.

For the Wari’ to be able to live on their land, it is necessary for them to possess some degree of mobility in order to benefit from forest resources dispersed throughout their territory. This need for mobility conflicts with the governmental policy of concentrating the population in a few permanent villages, at sites providing easy access to its visiting administrators. Some of these sites do not possess local soil adequate for cultivation: this applies specially to maize crops, the basis of Wari’ subsistence, which demands a special soil type known as black earth. Fertile soil, game, fish, firewood and other resources quickly become depleted in the areas surrounding these permanent and densely populated posts, provoking a negative impact on people’s diet and health, which in turn reduces growth of the indigenous population. In response, to this situation, the Wari’ are starting legal proceedings demanding return of part of their traditional territory on the shores of the Pacaas Novos and Ouro Preto rivers, today occupied by squatters breeding cattle. The aim of this process is to found new villages, overcoming the scarcity of alimentary resources and the high incidence of illness.

Agricultural technicians and other functionaries from Funai have set up a number of programs for stimulating the extraction of rubber and Brazil nuts, collective swiddens and agricultural production for market. Results of these projects are varied. Acquiring money for the purchase of ammunition, fishing gear, clothing and other goods comprises a constant problem for the Wari’. Many families collect and sell rubber and Brazil nuts, but the instability in prices prevents them from depending on these as stable income sources. Older people receive a pension, while young people sometimes obtain money through temporary work for Funai or for neighboring farmers and rubber tappers. The commercialization of forest resources is a polemical topic. In the last few years, some Wari’ have pressured Funai to allow the selling of wood, but these people have met opposition from many of their fellow Wari’. Until now, Funai has remained firm in its decision to prohibit the marketing of wood in any large scale and thus avoid exploration of the Wari’ and their resources by commercial businesses.

Note on the sources

The first anthropological studies were undertaken by two ethnographers who lived with the Wari’ at the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s. Alan Mason studied the Pitop community (today Tanajura) and his doctoral thesis focuses on OroNao social organization and kinship. Bernard Von Graeve’s doctoral thesis concentrates on the history of contact between the Wari’ and national society, with a special emphasis on the history and organization of the Sagarana community, administrated by the Catholic Church. This thesis provided the basis for his book The Pacaa Nova.

In 1986, Denise Maldi Meireles completed her master’s dissertation in social anthropology at the University of Brasília, based on interviews conducted in various Wari’ communities (‘Os Pakaas-Novos’). It deals with topics such as social organization, personhood, mythology and cannibalism. In 1989 she published a historical study of the occupation of the Guaporé river region: Guardiães da Fronteira.

Beth Conklin undertook research from 1985 to 1987 in the community of Santo André and four other Wari’ villages. Her doctoral thesis in medical anthropology, ‘Images of Health, Illness and Death Among the Wari'’, analyzes experiences of illness in Wari’ society before and after contact, as well as conceptions of the body in Wari’ social relations, illness and funerary cannibalism – work which she has continued in various later articles. Her book, Consuming Grief: Mortuary Cannibalism in an Amazonian Society, published by the University of Texas Press, explores the way in which endocannibalism makes up part of a mourning process involving ideas of bodies, spirits, memory and the psychology of suffering.

Aparecida Vilaça started her field research among the Wari’ in 1986, basing herself primarily in the village on the Negro-Ocaia river. Her master’s dissertation, completed in 1989 at the National Museum, UFRJ, was published as a book, Comendo como Gente, in 1992. It comprises a study of Wari’ cannibalism, in both its literal and figurative forms, with an emphasis on cosmology, warfare, shamanism and rituals. Her doctoral thesis in social anthropology, ‘Quem somos nós,’ analyzes the question of identity and the definition of the categories of stranger, enemy and White before, during and after pacification, contact and conversion to Christianity. She has published several articles on these and other questions.

In 1996, Marlene Rodrigues Novaes (Unicamp) wrote a master’s dissertation in social anthropology based on five weeks of fieldwork in the Lage I.P. community: ‘A Caminho da Farmácia.’ It focuses on indigenous representations of illnesses and treatments, as well as the relationships between Wari’ medicine and the Funai health services.

Since the 1950s, the Wari’ language has been studied by missionaries from Brazilian New Tribes Mission, who have produced an orthography, transcribed parts of the Bible and prepared workbooks and other didactic materials. Their work on the Wari’ language finally became available with the publication of a descriptive grammar, Wari’: The Pacaas Novos Language of Western Brazil, written by Daniel Everett, a linguist from the University of Pittsburgh, and Barbara Kern, a linguist from the New Tribes Mission who has worked with the Wari’ since the beginning of the 1960s.

Basic references to the Txapakura peoples can be found in older works, such as the chapters from Métraux, ‘Tribes of eastern Bolivia and the Madeira Headwaters: The Chapacuran Tribes,’ and Lévi-Strauss, ‘Tribes of the right bank of the Guaporé River,’ in the Handbook of South American Indians; the Ethno-Historic Map by Curt Nimuendajú and his article ‘As Tribus do Alto Madeira;’ ‘Notes on the Moré Indians, Rio Guaporé, Bolívia,’ by Rydén; the books El Itenez Salvaje by Leigue Castedo; Atiko y by Snethlage; and Nordenskiöld’s article ‘The Ethnography of South-America seen from Mojos in Bolivia.’

Sources of information

- CAMPOS, Mônica Soares de. Estudo da correlação mercúrio-selênio em amostras de cabelos de índios Wari. São Paulo : USP-Ipen, 2001. 100 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- CATHEAU, Gilles de. Os Warí : subsistência, saúde e educação. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 559-61.

- COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos E. A.; ESCOBAR, Ana Lúcia. Considerações sobre as condições de saúde das populações das Áreas Indígenas Pakaanova (Wari) e do Posto Indígena Guaporé, Rondônia. Porto Velho : UFRO, 1998. 22 p. (Documento de Trabalho, 1)

- CONKLIN, Beth A. Body paint, feathers, and vcrs : aesthetics and authenticity in Amazônia activism. American Ethnologist, Washington : American Anthropological Association, v. 24, n. 4, p. 711-37, 1997.

- --------. Consuming grief : compassionate cannibalism in an Amazonian society. Austin : Univ. of Texas Press, 2001. 316 p.

- --------. Consuming images : representation of cannibalism in the Amazonian frontier. Anthropological Quarterly, s.l. : s.ed., v. 70, n. 2, p. 68-78, 1997.

- --------. Hunting the ancestors : death and alliance in Wari'cannibalism. Lat. Am. Anthropol. Rev., s.l. : s.ed., v. 5, n. 2, p. 65-70, 1993.

- --------. Images of health, illness and death among the Wari (Pakaas Novos) of Rondonia, Brazil. São Francisco : University of California, 1989. 583 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. O sistema médico Warí. In: SANTOS, Ricardo Ventura; COIMBRA JÚNIOR, Carlos E. A. (Orgs.). Saúde e povos indígenas. Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, 1994. p.161-88.

- --------. Thus are our bodies, thus was our custom : mortuary cannibalism in an Amazonian society. American Ethnologist, Washington : American Anthropological Association, v. 22, n. 1, p. 75-101, 1995.

- --------; MORGAN, Lynn M. Babies, bodies and the production of personhood in North America and a Native Amazonian Society. Ethos, s.l. : s.e.d, v. 24, n. 4, p. 657-94, 1996.

- ESCOBAR, Ana Lúcia. Epidemiologia da tuberculose na população indígena Pakaa Nova (Wari), Estado de Rondônia. Rio de Janeiro : ENSP, 2001. 147 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- EVERETT, Daniel; KERN, Barbara. Wari : the Pacaas Novos language of Western Brazil. London : Routledge, 1997.

- GRAEVE, Bernard von. The Pacaa Nova clash of cultures on the brazilian frontier. Ontário : Broadview Press, 1995. 160 p.

- LEIGUE CASTEDO, Luis. El itenez salvaje. La Paz : Ministerio de Educación y Bellas Artes, 1957.

- LEVI-STRAUSS, Claude. Tribes of the right banl of the Guaporé river. In: STEWARD, Julian H. (Ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. v.3. Washington : Smithsonian Institution, 1963. p. 371-9.

- MALDI MEIRELES, Denise. Guardiães da fronteira : rio Guaporé, século XVIII. Petrópolis : Vozes, 1989.

- --------. Os Pakaãs-Novos. Brasília : UnB, 1986. 525 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- MASON, Alan. Oronao' social structure. Davis : University of California, 1977.

- MÉTRAUX, Alfred. Tribes of eastern Bolívia and the madeira headwaters : the Chapacuran tribes. In: STEWARD, Julian H. (Ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. v.3. Washington : Smithsonian Institution, 1963. p. 397-406.

- NIMUENDAJÚ, Curt. Mapa etno-histórico de Curt Nimuendajú. Rio de Janeiro : IBGE/Fundação Nacional Pró-Memória, 1981.

- --------. As tribos do Alto madeira. In: --------. Textos indigenistas. São Paulo : Loyola, 1982. p.111-22.

- NORDENSKIÖLD, Erland. The ethnography of South-America seen from Mojos in Bolivia. Comparative Ethnographical Studies, s.l. : s.ed., n. 3, 1924.

- NOVAES, Marlene. A caminho da farmácia : pluralismo médico entre os Wari' de Rondônia. Campinas : Unicamp, 1996. 254 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- PRATES, Laura dos Santos. O artesanato das tribos Pakaá Novos, Makurap e Tupari. São Paulo : USP, 1983. 149 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- RYDÉN, Stig. Notes on the Moré indians, rio Guaporé, Bolívia. Ethnos, Estocolmo : s.ed., n.2/3, 1942.

- SANTOS, Elisabeth C. Oliveira et al. Avaliação dos níveis de exposição ao mercúrio entre índios Pakaanova, Amazônia, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro : Fiocruz, v. 19, n. 1, p. 199-206, jan./fev. 2003.

- SNETHLAGE, E. Heinrich. Atiko y. Berlim : Klinghardt & Biermann Verlag, 1937.

- VILAÇA, Aparecida Maria Neiva. O canibalismo funerário Pakaa-Nova : uma nova etnografia. In: VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo; CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da (Orgs.). Amazônia : etnologia e história indígena. São Paulo : USP-NHII ; Fapesp, 1993. p. 285-310. (Estudos)

- --------. Comendo como gente : formas do canibalismo Wari. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1992. 392 p. (Originalmente Dissertação de Mestrado, Museu Nacional, 1989)

- --------. Christians without faith : some aspects of the conversion of the Wari'(Pakaa Nova). Ethnos, s.l. : s.ed., v. 62, n.1/2, p. 91-115, 1997.

- --------. Cristãos sem fé : alguns aspectos da conversão dos Wari' (Pakaa Nova). Mana, Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional, v. 2, n. 1, p. 109-37, abr. 1996.

- --------. Cristãos sem fé : aspectos da conversão dos Wari' (Pakaa Nova). In: WRIGHT, Robin (Org.). Transformando os Deuses : os múltiplos sentidos da conversão entre os povos indígenas no Brasil. Campinas : Unicamp, 1999. p. 131-54.

- --------. Fazendo corpos : reflexões sobre morte e canibalismo entre os Wari' a luz do perspectivismo. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 41, n. 1, p. 9-68, 1998.

- --------. Quem somos nós : questões da alteridade no encontro dos Wari' com os brancos. Rio de Janeiro : Museu Nacional-UFRJ, 1996. 425 p. (Tese de Doutorado)

- --------. O sistema de parentesco warí. In: VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo (Org.). Antropologia do parentesco : estudos ameríndios. Rio de Janeiro : UFRJ, 1995. p. 265-320. (Universidade)

- --------. Os Warí. In: RICARDO, Carlos Alberto (Ed.). Povos Indígenas no Brasil : 1991/1995. São Paulo : Instituto Socioambiental, 1996. p. 556-8.

- VON GRAEVE, Bernard. The Pacaa Nova : clash of cultures on the Brazilian frontier. Peterborough, On : Broadview Press, 1989.

- --------. Protective intervention and interethnic relations : a study of domination on the Brazilian frontier. Toronto : University of Toronto, 1972.